Nouning a Verb

A common complaint by grammarians is about verbing nouns (meaning using a noun as if it were a verb), which you can actually do in English. For example, you can say “Let’s table the motion.”

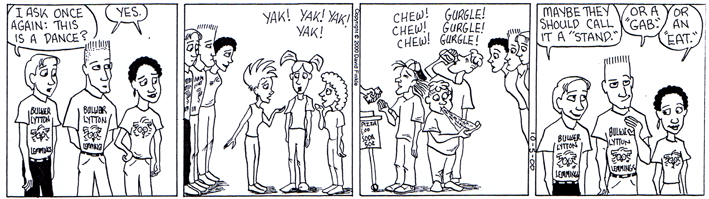

Looks like you can noun a verb, too. Here’s what I mean:

Subscribe to this blog's RSS feed

“S” not for Plural?

Not much of a lesson today, but slightly autobiographical.

I think, and have thought so for years, that “-s” being the ending on a singular verb is a little incongruous (weird), since it’s also the usual ending on plural nouns. I frequently see people whose first language isn’t English get this wrong. Can’t say as I blame them.

Anyway, here’s the Andertoons comic that reminded me about this.

Phrase out of Place

As a rule, you should put similar parts of a sentence together. For example, if a sentence has two subjects, put them together.

Tom and Dave played tag.

S S V DO

What happens when you don’t put them together? You get confusion!

Tom played tag and Dave

S V DO ?

Huh? Is “Dave” some new kind of game that Tom played? After all, it’s right next to the direct object.

That example is trivial, perhaps, so here’s an example from real life:

Access in divisional and functional areas is too broad in some systems, increasing security risks for potential misappropriation, due to IT [the Information Technology department] owning systems instead of the business areas.

Look at the part after “due to.” “IT” is the subject, “owning” is the verb, and “systems” is the direct object. What is “business areas”? I don’t think IT would be owning business areas, so let’s rewrite the sentence so you can tell that “business areas” is another subject:

Access in divisional and functional areas is too broad in some systems, increasing security risks for potential misappropriation, due to IT instead of the business areas owning systems.

That makes more sense! Go thou and do likewise.

Pet Peeve Day Three

My peevishness is aroused when people use transitive verbs as if they were intransitive, particularly “display” and “complete.”

Enough jargon. Here’s a definition by example:

When you display, you display something. When you complete, you complete something.

Back to jargon: That word “something” is called a direct object, and transitive verbs always have one. Intransitive verbs don’t have to have one: you can think, you can suppose, you can walk, you can appear or disappear (in a puff of smoke, perhaps), all without having to put something after them. That’s intransitive.

Here’s an article where they (The National Oceanography Centre in the UK) do it wrong in the headline, then do it right in the article (with a different verb, but you get the point):

The COMICS expedition completes

The first COMICS expedition reached a conclusion just before Christmas, having collected a great data set on biological carbon in the Ocean’s twilight zone.

I suppose we grammar curmudgeons will have to get used to this solecism, especially the one with “display,” because computer instructions are so common. But when you press Enter, the window doesn’t display, it appears!

Harrumpf.

Commas at the Beginning

You might find this post boring. It’s a straight-out grammar lesson.

Here are the rules:

- Separate interjections (such as “However, …”) and direct address (someone’s name or title) from the sentence with a comma.

- Separate an introductory clause from the rest of the sentence with a comma.

- Separate an introductory prepositional phrase from the rest of the sentence if it contains five or more words.

- Some common shorter prepositional phrases, such as “for example,” get the comma, too. This rule is flexible. If you have a short prepositional phrase, and it feels as if it needs a comma, go for it.

Okay, take a look at this:

However, the Coppersmith’s algorithm allows quite a lot of flexibility. Tom, you can’t do that!

Easy enough. Now how about this one:

To speed up the prime number generation, smart card manufacturers implement various optimisations.

(British spelling. Ignore that). The sentence starts with “to.” Prepositional phrase, right? Well, no. It’s actually an infinitive. Infinitives are verbs. If it has a verb, it’s a clause. So I could rewrite this as:

To speed things up, smart card manufacturers implement various optimisations.

Fewer than five words, still gets the comma. If fact, look at a sentence I just wrote:

If it has a verb, it’s a clause.

“Has” is a verb, so you have a clause. A lot of introductory clauses start with words like “if” and “when.” We call them introductory adverbs. In fact, if you got rid of that introductory adverb, you’d have a complete sentence, which requires a period, not a comma. If you write:

It has a verb, it’s a clause.

Get rid of that comma! Use a period! Two independent sentences separated by a comma is called a comma splice, and that’s a no-no.

Sorry—it’s pretty hard to find a comic about commas.

PS—Wouldn’t you know! I ran into one at Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal: