Singular or Plural?

The rule for agreement is that a singular subject gets a singular verb, and plural subject gets a plural verb—even when a differently numbered phrase intervenes. But exceptions exist!

Sometimes a plural can be treated as a singular. In the past I mentioned that some company names, that end in “& Co.” are treated as singulars.

Here’s a sentence (from a Facebook post, so I can’t link to it) in which the writer, Dr. Bill Stillwell, an MD, defines a plural as a singular:

Renal damage, up to 50% of ICU patients was also seen, possibly from the high concentrations of ACE2 receptors found in the kidneys (used by the virus to effect cell entry) and 5-10% of patients required dialysis.

What was seen? Not the patients (plural), but the damage (singular). (Myself, I’d have inserted “in” before “up.”)

Here’s another one, on page 75 of the March 2020 Scientific American. It’s a bit trickier:

Our concepts of how the two and a half pounds of flabby flesh between our ears accomplish learning date to Ivan Pavlov’s classic experiments, where he found that dogs could learn to salivate at the sound of a bell.

The writer is obviously referring to the brain, a single thing, even though he called it a number of pounds of flesh, a plural.

Was he right? “Pounds” is plural, but they don’t act separately (do they?). Feel free to comment in the comments.

Subscribe to this blog's RSS feed

A Sentence Out of Order

A rule in English is to put modifiers as close to what they modify as you can. Adjectives generally go directly before the noun they modify, a blue car, for example. (Except for post-positives such as “malice aforethought.”)

Adjectival phrases can go afterwards, but what do you do when you have more than one of those phrases? You put the phrase as close as you can to the thing it modifies. Here’s a guy who didn’t:

Decades ago, psychologist Benjamin Libet monitored subjects’ neural activity while they chose to hit a button, and he discovered a burst of activity preceding the conscious decision to push the button by a split second.

https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/cross-check/my-go-to-arguments-for-free-will

What does that split second refer to? It refers to the burst of activity, not pushing the button! He didn’t need so many big words, either. How about this:

… he discovered a burst of activity a split second before the decision to push the button.

Well, I think the sentence is easier to follow now.

This sort of thing is part of good writing. No clear-cut rule, just good judgement.

- When you write, think how you might be misunderstood, and don’t do that.

- Try not to cause bumps for your reader.

Figures of Speech in Expository Writing

When you write to explain something, your goal is to be clear, not necessarily beautiful or picturesque. Some figures of speech are so common we don’t think of them as such; see the use of “window” in the sentence below. But how about the word “born”?

Because the cesium-rich particles were born early in the meltdown, they offer scientists an important window into the exact sequence of events in the disaster.

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/radioactive-glass-beads-may-tell-the-terrible-tale-of-how-the-fukushima-meltdown-unfolded

Being born is normally a biological term. Might be a little better to have said “…particles were created,” eh? Or how about getting rid of the passive while we’re at it, and say that the particles formed early in the meltdown?

Not as distracting now, is it?

Rule of thumb: The more technical you are, the less poetic you should be.

Here’s a photo of the event:

The Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power plant after a massive earthquake and subsequent tsunami on March 14, 2011 in Futaba, Japan. Credit: Getty Images

Compose and Comprise

I have written about both of these words in the past (look them up in the search box in the upper right) but I found both of them in the same sentence, and they’re both correct! Couldn’t pass it up.

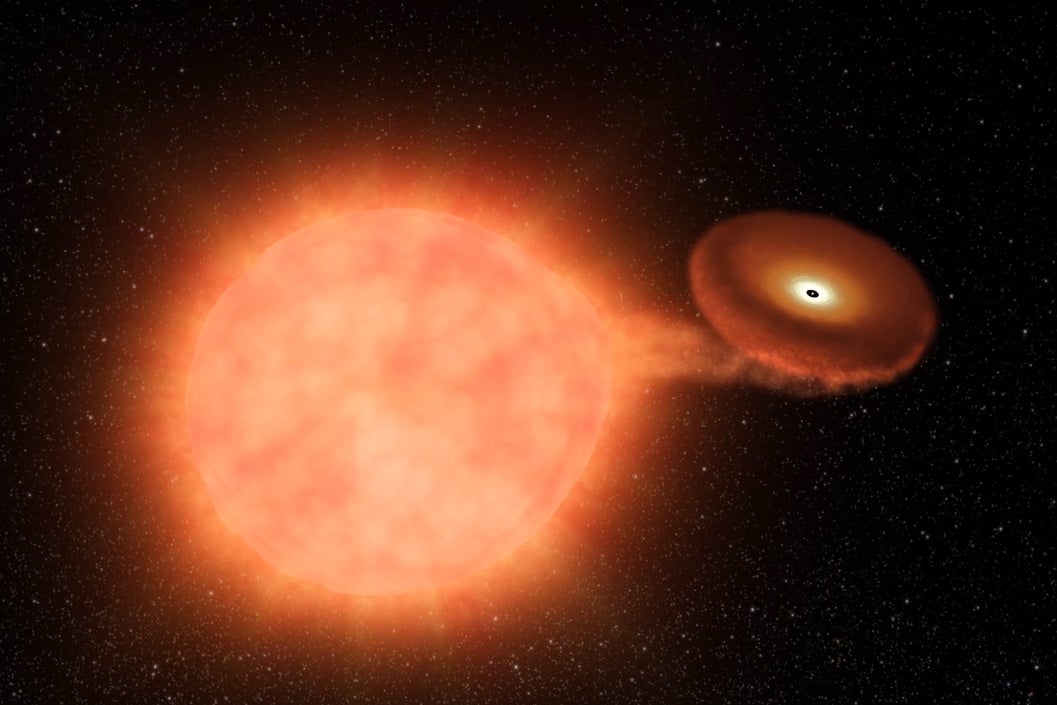

Whereas typical white dwarfs comprise carbon and oxygen, these stars are mostly composed of neon.

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/zombie-stars-shine-on-after-mystery-detonations/

—In a Scientific American article, naturally. They’re usually pretty good about getting these things right.

Remember the rules:

- Comprise goes from the whole to a list of parts

- Composed of goes from parts to the whole

- Never use “comprised of”! It’s a pretentiousism.

I like pictures, so here’s one from the article. The sentence refers to the single-pixel white spot in the middle of the donut. Look closely.

Credit: NASA and JPL-Caltech

PS—For you picky, detail-oriented editors out there—The sentence refers to the dwarf star represented by the single-pixel white spot.

Another Correct “Whom”

A lightweight post today (after all, I mention this feature of English grammar rather often). Actually it’s whomever. But it’s correct!

You could even say the “whomever” is correct for two reasons:

- The noun clause “whomever she wants” is the direct object of the main verb, “can date.”

- “Whomever” itself is the direct object of the noun clause’s verb, “wants.”

The second reason is the real reason, by the way.

Why is the second reason the real one? The rule is this: you go from the inside out. Rule 2 describes what’s going on inside the clause, which is inside the sentence.

Here’s a sentence with similar construction that uses “who” to begin a noun clause that’s a direct object, and it’s correct:

Detailed new risk maps show who should really flee a threatening storm.

Scientific American Oct 2018, page 1

“Who” is the subject of the verb “should flee,” inside the noun clause. The noun clause is the direct object of “show.”