The Second Most Common Mistake

—in English! In English! I’m sure this is nowhere near the top of the list of mistakes humans make. This might not even be second on the English grammar list, but I think it comes right after the one where someone, trying deliberately to be high-class, says “between him and I.”

This error is using “whom” when “who” is actually correct (or in this case, “whomever” and “whoever.”). First, the rule: when you have a subordinate clause, work from the inside out. Here’s an example of the mistake, from Edge of Adventure. Look at the first panel in the bottom row. Can you tell why he should have said “whoever”?

Yes, “to” is a preposition, and the clause that comes after it is its object. But that clause has its own subject and verb! And since we work from the inside out, being the subject of that clause takes precedence over the whole clause being an object, so it’s “whoever did this.” If you really want a “whom” in that sentence you could say something like “…to whomever I find on the trail.” Now “I” is the subject, and “whomever” is the direct object of “I find.” Make sense?

So sometimes you have permission to use “who.” Be careful.

Subscribe to this blog's RSS feed

Compound Objects

I suppose this Beetle Bailey comic is a repeat of the second-oldest joke in the book, descending as it does from sixth grade English (Hi, Mrs. Clemens!). Lots of folks get confused when they have two objects of a single preposition, and the mistake is so common that I decided to repeat the joke as a reminder. The trick, by the way, is to think the phrase without mentioning the other guy; then it’s easy to get the correct word.

The other second-oldest joke, I suppose, is the one about the restaurant manager who goes someplace else to eat.

What??? You want to know the world’s oldest joke? Well, just between you and (ahem) me, it’s somewhat scatological, so I won’t repeat it here, but they found it on a cuneiform tablet that dates to about 4000 years ago. Google “oldest joke.” Reuters has a short article about it.

Watch your subject

The rule is that if you have a singular subject, you must have a singular verb. (And if you have a plural subject, the verb must be plural.) We call it subject-verb agreement. Take a look at this sentence:

By July 15, an average of 2,500 tons of supplies was being flown into the city every day.

It’s from a passage in This Day in History for June 26. Is the sentence correct or not?

It’s an easy sentence to get wrong, but they got it right! The subject is average, not tons, and not supplies. The latter two words are objects of prepositions, so neither can be the subject of the sentence. So average has to be the subject.

Be careful out there. Those prepositional objects’ll get you if you’re not alert.

Why People use “I” after a Preposition

Because your grade-school English teacher corrected two mistakes at once.

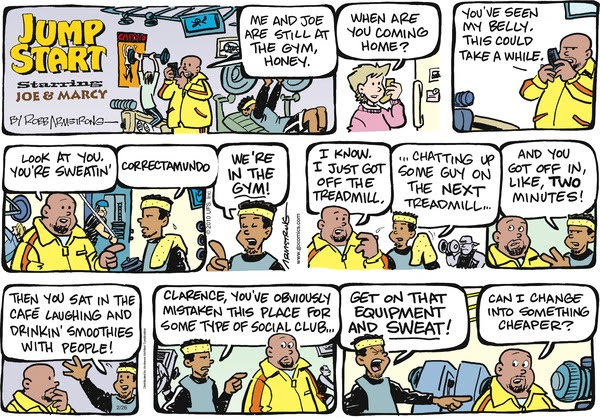

You’d say something like the first three words in this Jump Start comic by Robb Armstrong:

The first “mistake” is putting yourself first when you mention yourself and someone else. Putting yourself first is perfectly grammatical; doing so isn’t humble, though. In our culture, we think mentioning yourself last is more polite, but I have seen scientific writing in which the team leader put himself first. Something like “I and my colleagues performed a series of experiments,” which makes sense if the colleagues were only helping out.

The second mistake is a real one, using “me” as the subject. If you hadn’t happened to mention that other person, you wouldn’t have gotten it wrong—no ones says “Me went to the store.” Well, unless they’re being deliberately funny.

The problem is that correcting two things at once is a bit of overload for a young mind, so you don’t notice that you have a compound subject in the corrected sentence, and later when you mention your friend and yourself after a preposition, you follow the whole double correction and say something like “The teacher really gave it to Tim and I.”

I remember being in a car once with a bunch of students, and I happened to use “[someone] and me” after a preposition, and one of the students delightfully corrected me for saying “me.” I praised her for being alert, and explained my sentence with a short version of this post. I have no idea whether any of the occupants of the car changed their manner of speaking. Oh well.

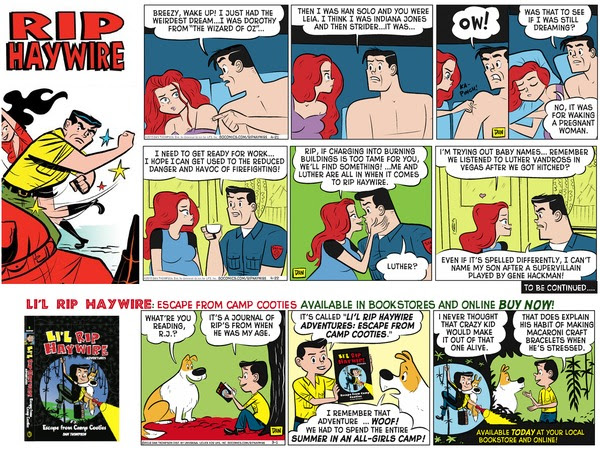

PS—wouldn’t you know, I ran into this same mistake the same day I saw that Jump Start. This one is Rip Haywire. The mistake is in the middle of cell 5, though I think some of you can relate to the top row of cells…

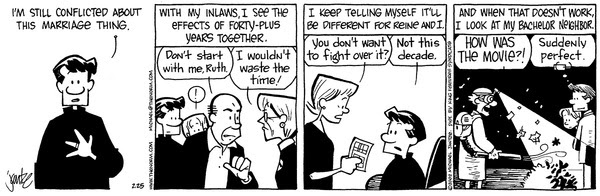

…and here’s someone, The Norm, who made the “corrected” mistake. Cell 3:

An Interesting Comment

I hardly ever get comments to this blog, but I posted a link to one of my posts on Google+ the other day, and a friend made a comment that’s not only worth repeating, but it deserves a post! Go follow the link if you want to see the cause for the comment. Here’s his comment:

I think I get it right most of the time…but still have a hard time saying, “Whom do you think you are!?”….the other thing you taught me and I keep forgetting is where the quote marks go in a sentence…not sure I got it right above…

Lorin Walker (a former boss, by the way, and still a friend) says he has trouble saying “whom do you think you are?” Well, he should have trouble saying that, but not for the reason he thinks! We usually put the subject first in English, and the nominative (subject) form of the word is indeed “who.” So we’re used to putting “who” at the beginning of a sentence.

With questions, however, the subject generally doesn’t come first, the object does, and that’s where “whom” comes in. So you generally start a question with “whom.” Except for one thing: the type of verb.

Remember predicate nominatives? They look like direct objects, except they go with linking verbs (mainly some form of “to be” but also other verbs that are equivalent to an equals sign, such as seem and appear.) So in Lorin’s example sentence, the first word goes with (is the predicate nominative of) the last word, “are”! He could say “Who do you thing you are?” with impunity, and be so correct that he’d fool a lot of amateur grammar nazis.

PS: I just now saw a headline, in the Los Angeles Times, no less:

Who does your member of Congress support for president?