Five Kinds of Bad Words

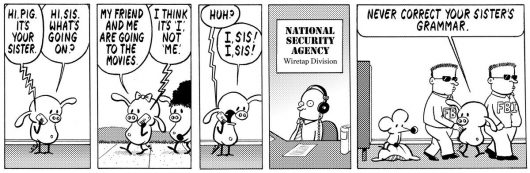

This comic, Tina’s Groove, made me think of today’s post:

I was going to write about four kinds of bad words, but then I thought of a fifth. So here are five types of words that ought never appear in expository writing. (Yet I’m going to mention examples of these, and this post is expository. I guess using them as examples isn’t the same as actually using them. (This conundrum reminds me of Gödel’s proof, part of which proves that contradiction is inherent in all logical systems.) But I digress.)

Profanity. Profane is the opposite of holy. Profane means something like “having nothing spiritual about it.” We call profanity “four-letter words,” “Anglo-Saxon,” obscenities,” “dirty.” Well, lots more euphemisms than those four; Google them if you like. The strength of a profane expression is in how unacceptable in polite company the word is. In fact we have a whole vocabulary of profane expressions designed specifically to express different degrees of shock value, apparently to match one’s degree of disgust with one’s degree of politeness. The latest one, I think, is “Oh snap!” Pretty hard to connect that with anything dirty. We call these mild forms of profanity “minced oaths,” by the way. Apparently there’s a word for everything!

Oaths, also called swearing. Yes, these terms are frequently used interchangeably with profanity, but there’s a technical difference. You swear an oath. Technically an oath is a type of promise in which you either call down some penalty on yourself if you’re not telling the truth, or you call on a higher authority to witness that you’re telling the truth. The verb is “swear,” and the noun is “oath.” These are oaths that you can swear:

- Cross my heart and hope to die, stick a needle in my eye

- By Jove!

- I swear on my mother’s grave!

- …so help me God

Real, conscious, sworn oaths aren’t necessarily bad, but they generally aren’t appropriate or necessary for explaining things, either.

Curses. A curse is a wish that harm will befall someone. (Or something. You can curse your computer, for example.) You can mince curses, too. You can say “Go jump in the lake,” or “Go to h-e-double toothpicks,” or “Why don’t you take up residence in Tophet?” Some curses aren’t quite obvious: “Just wait until you have teenagers!” My favorite curse is “I hope your grandchildren take up motorcycling.” I mutter it under my breath when someone in a car tries to kill me. But I don’t use curses when I explain something.

Insults. An insult is a way of telling someone that they are distasteful. The westerns of yesteryear were pretty creative with their insults. “Why you no-good yaller, lily-livered skunk, you” comes to mind. Shakespeare was pretty colorful with his insults. In fact I recall a website where you can construct your own in his style. Here’s another with referenced quotes. The best insults are ones when the insulted person doesn’t realize they’re being insulted. “I highly recommend you to my mother-in-law” has been used on at least one occasion. Some insults are unintentional or ambiguous, or intended to be humorous, so take care not to take offense easily if you think someone has insulted you. When you explain something in writing, you won’t insult someone by making it simple. They can always skip over that part.

Lies. You know what lies are, and lies come in degrees same as everything else listed in this post. The key is the intent. If you want someone to believe something that’s not so, it’s a lie. Being incorrect isn’t lying, but it’s a good idea to be correct or give fair warning about the possibility of error. Saying something that isn’t literally true isn’t a lie if it’s, say, a figure of speech, or understood to be humor. I guess parental exaggerations fall into this category: “I hope your face doesn’t freeze like that!” I’m a technical writer by trade, and I tell people that “I tell the truth for a living,” and every statement in this post is the truth. Except one.

Subscribe to this blog's RSS feed

Beware Statistics

You know the old saying about three kinds of lies, Lies, Dirty Rotten Lies, and Statistics. (Okay, the second one uses a four-letter word). Statistics are tricky (or dangerous) because you can truthfully describe something and still mislead. In high school I read a book, How to Lie with Statistics by Darrell Huff. It’s a pretty good intro to the topic. I ran into an article the other day that can illustrate the trickiness of statistics two ways. First the passage in question:

The researchers found that compared to participants who watched TV less than 2.5 hours each day, deaths from a pulmonary embolism increased by 70 percent among those who watched TV from 2.5 to 4.9 hours; by 40 percent for each additional 2 hours of daily TV watching; and 2.5 times among those who watched TV 5 or more hours.

Sounds dangerous, doesn’t it? A 70% increase! Here’s the misleading part: What’s the percentage of getting the embolism in the first place? It turns out to be roughly one in a thousand. So a 70% increase of that is still less than two in a thousand. Not so bad now, eh? The trickiness is that

even a large increase of a small amount is still a small amount.

We’re not finished. Let’s look at absolute numbers instead of percentages. The population of the US is about 319 million. That makes that one in a thousand to be roughly 319,000. Add 70% to that and it’s more than half a million! How would you like to pay the medical bills for half a million people? The principle here is that

if the numbers are large enough, even a small percentage is still pretty big.

For an engaging book that goes into these and other principles for understanding statistics, I suggest How not to be Wrong: The Power of Mathematical Thinking by Jordan Ellenberg.

So what does all this have to do with expository writing?

When you write, make sure you don’t mislead your readers.

Another Mistake not Made

A solecism that high school English teachers love to warn against is starting a sentence with “hopefully,” as in

Hopefully, we’ll all be in time for the meeting.

This is really just an instance of a fairly common problem, using an adverb when you need an adjective. You see it a lot in the news with “reportedly.” I googled that word recently and was chagrined to see how much it was misused. You can misuse many adverbs this way. Start some sentences with “understandably,” “supposedly,” “thankfully,” and “unexpectedly” for other examples.

Anyway, here’s someone who did it right! I put the correct usage in bold.

That possibility, one would hope, should weigh heavily upon the minds of the Supreme Court justices, who once praised those who “build and create by bringing to the tangible and palpable reality around us new works based on instinct, simple logic, ordinary inferences, extraordinary ideas, and sometimes even genius.”

Dignified sentences like this one are just as easy to read as ones that start with an understandably incorrect adverb.

Censorship

I recently made a reference to “comic sensors,” and I guess I understand an editor’s desire to keep something read by children free from words generally considered unsuitable for young vocabularies. But we hear lots of stuff on TV that everyone gets exposed to, and references to many things (such as politicians and current events) are not considered equivalent to taking a position on them.

Here’s an example of an instance when these censors (I won’t call them editors) went rather too far, in my opinion.

This Pearls Before Swine comic, by the excellent (read horrible) punster Stephen Pastis, got pulled. (Follow the link for the NCAC article about it.) C’mon, guys, we hear that word all the time. It’s okay to make fun of ISIS. Or maybe I should ask the NSA to lighten up, too?

PS—I ran into another strip, The Argyle Sweater, that’s sort of about censorship. Can’t really say I object to this one…

Ambiguity is a no-no

Ambiguity is when something can be understood in more than one way. Ambiguity has its place in humor, when you are frequently led to expect one thing, and then something else happens. Puns rely on ambiguity by definition. Ambiguity belongs in poetry, which not infrequently means two or more things at once. Figures of speech are a type of ambiguity, where the surface meaning is understood not to be meant. You even find ambiguity in advertising, when they want to make you think the product is better than it is. (Sometimes it’s worse than mere ambiguity. Read this article about deliberate obfuscation called Dark Patterns.

I leave it as an exercise for the reader to come up with examples of these. (Some will be trivial, some you might have to think about for a while.) Okay, here’s one example, from my good buddies, Frank and Ernest:

But in expository writing, when you’re explaining something, you want to avoid ambiguity as much as you can. My first rule of good writing is to be clear. (This and the other four are in the essay I mention in the right margin.) Work hard to avoid being misunderstood. Ponder how what you write might be misinterpreted. Get someone to read the material. The rule is that when you have someone read what you wrote, if they get something wrong, the problem is in the writing. That’s why editors are so valuable. I have a related rule that I post on my wall:

Bad writing must never be justified with the claim that the reader will figure it out.

This policy of getting someone else to read your stuff is more important than you might think. I read a Scientific American article recently that called to mind the trickiness of removing ambiguity all by yourself. Look at this sign:

Being a bicycle sympathizer, this ambiguity never occurred to me: Is it telling drivers to watch out for bikes, or is it reminding bicyclists that they don’t own the road? Apparently enough drivers thought the sign was telling bicyclists to stay out of the way that transportation departments are putting up signs that say something like “Bicyclists may use full lane.” The article also mentioned that some people interpret the phrase “antibiotic resistance” to mean one’s body becoming resistant to the curative effects of antibiotics instead of germs resisting the lethal effects of antibiotics on themselves. Read the article to find out how the medical community is being encouraged to get around this one.

Here’s the point: Do everything you can to prevent misunderstanding: proofread, try to think of ways to get it wrong, and have another person read your writing.

Do I make myself clear???